How Guns Made America Great …(and Rich)

There is a major aspect of the relationship between America and guns that isn’t much known or celebrated, but should be. Guns were the seed that spawned the Industrial Revolution on these shores. Tweet

Highlights

When I hold my Pennsylvania long rifle, I feel like I have American history itself in my hands.

You can’t tell the American story and leave out guns. Without them we would be singing “God Save the Queen,” and pretending to like tea

Long before Henry Ford was making cars on an assembly line, guns spawned the American Industrial Revolution

Colt was one of the pioneers in implementing mass production techniques. His factories were state of the art.

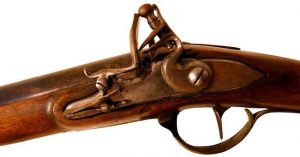

I own guns. Not as many as some people, but enough to make people who don’t know about guns—but have strong opinions anyway—uncomfortable. While these people are not always easy to reason with, it might reassure at least a few of them to know that my favorite gun is no more likely to turn up at a mass shooting or even a drive-by than a Nerf gun, water pistol or, for that matter, a frying pan.

It is a black powder, flintlock musket. A fifty-caliber Pennsylvania long rifle. Loaded from the muzzle. The powder followed by a ball and patch which you force down with a ramrod. Then you prime the pan, cock the hammer, set the trigger and fire. It is an almost choreographed series of moves and even at my steadiest, I am lucky to get off three shots a minute.

Yet it was, arguably, the decisive weapon in the American Revolution.

Quick story. In October of 1777, in what would be the decisive engagement of the conflict, Battle of Saratoga, the Redcoats were early on having the better of the Colonial army, one element of which was “Morgan’s Riflemen.” They were under the command of legendary frontiersman Daniel Morgan, and carried Pennsylvania long rifles. The British musket – known as the “Brown Bess” – had an effective range of some 50 yards; Morgan’s men were lethal out to 300 or more.

When General Benedict Arnold, still on our side at the time, saw the battle was going badly for the Colonials, he had Morgan order one of his best shooters to aim for the British commander, conspicuous on his white horse more than 250 yards away. He doubtless believed the range made him invulnerable.

Morgan’s man made the shot. The battle turned. Back in England, people were appalled. Such long-range killing was considered unsporting. Arnold went on to a career in treason. The American republic was born.

When I’m out with my Pennsylvania long rifle, the connection to its most legendary practitioners, the men who marched with Daniel Morgan, is palpable.

You can’t tell the American story and leave out guns.

You can’t tell the American story and leave out guns. It would be like trying to tell the story of France without wine or cheese or Napoleon. America was built on guns. Without them we would all be singing “God Save the Queen,” and pretending to like tea.

Guns – American guns – not only made victory in the Revolution possible, they made the western expansion possible. Whether or not that was a good thing, or done honorably, is open to discussion. Whether or not it could have been accomplished without guns is not. The side that won the Battle of the Little Bighorn, ironically, was the one that was armed with the better – and American made – guns, in this case Henry repeating rifles.

It is not for nothing Americans wrote guns into the Constitution. Or that so many American presidents, including John F. Kennedy, were gun aficionados. One great American president – Teddy Roosevelt – might be accurately described, in the current Left-of-center vernacular, as a “gun nut.”

There is another aspect of the blood-kin relationship between America and guns that isn’t in many ways as celebrated, but should be. Guns were the seed that spawned the Industrial Revolution.

Long before Henry Ford was making cars on an assembly line, factories along the Connecticut River were using the river’s hydraulic power to mass produce guns. One of the essentials of mass-production is, of course, the use of interchangeable parts. The engine block of, say, one Chevy 350 is the same as another. And the cylinders or crankshaft from one will fit any other. The principle was widely understood, in theory, before Eli Whitney validated it, conclusively, shortly after the American Revolution.

Trick was making it work.

In 1801, Whitney built ten guns made of identical parts. Then, in a dog and pony show, he disassembled them in front of Congress, mixed the parts up in a pile, and proceeded to put them back together, into ten functioning guns—with no parts left over.

Skeptics say that Whitney had help, that he somehow cheated, which is something of a tradition when it comes to the landing of defense contracts. Also, the parts that the ten guns were built from had all been hand made. Still …

The momentum toward what became mass production was now irresistible. Factories sprang up along the Connecticut River, where the Industrial Revolution began on these shores.

Whitney’s name is, of course, more closely associated with cotton than with guns. Not so the name “Colt.”

Many people, if they think about it at all, associate that name with the famous aphorism, “God created man, but it was Sam Colt who made them equal.”

Already this is a great American story. And it gets better.

Colt became one of the great pioneers and implementers of mass production techniques. His factories were – in a phrase that was not yet in currency – “state of the art.” It is fair to say that the Colt Armory in Hartford, Connecticut was the first plant to employ what became known as an “assembly line.”

Other huge factories with names like Winchester and Springfield soon lined the Connecticut River.

Colt and others were the aristocracy of American gun making. Just as Henry Ford’s factories later built cars for the people who worked in them, they built guns for the masses.

It was mass production that made the American middle class and societal egalitarianism possible.

There is a little museum in the town of Windsor, Vermont, not far from where I live, called the American Precision Museum. It’s a monument to the great societal sea-change that was brought about by the advent of the assembly line and mass production. These are not such romantic notions these days as they once were, when the alternative was a hard life on the farm or in apprenticeship. But it was mass production that made the American middle class and societal egalitarianism possible. It revolutionized things in a way that was not matched by any technological change until, perhaps, the dawn of our new digital age.

I thought about this when I visited the American Precision Museum. There is something almost touching about the tools on display there, they look so innocently primitive. But it was those machines that would make possible the mass production of everything from sewing machines, to typewriters to automobiles. They changed life for the better in every city, town and village in this country, they spawned the vast middle class. They made America great.

And it all started with guns.