File Under Tough Beginnings – And Mentors to Help Us Through

David Black, deep into a successful career as a novelist and TV producer, looks back on the frustrations and failures at the start—and the celebrated writer who helped him through them. Tweet

Highlights

“By the time I knew him, Burgess had a ruined face—heavy lidded (a little like Paul McCartney if McCartney had lived Keith Richards’ life).”

Tillie Olsen: “Writing is so hard, we should honor anyone who has the courage to try.”

“Burgess encouraged all of his students, trying to teach them how to get from here to there.”

“This was the sixth, unpublished novel I had written. ... I was desperate.”

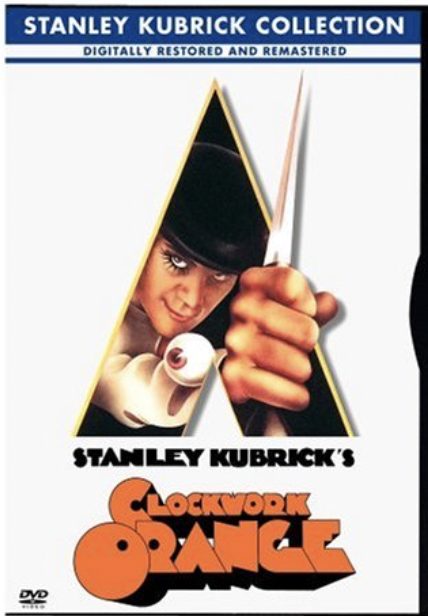

Editor’s Note: author David Black would go onto a highly successful career as a novelist and producer of such classic, TV shows as “Hill Street Blues” and “Miami Vice.” But he began, as we all do, as an aspirant. That is when he was lucky enough to cross paths with the celebrated Anthony Burgess—author of, among many others, “A Clockwork Orange,” the original dystopian novel and basis of the classic film by Stanley Kubrick.

“Do you want to collaborate on a dirty book?” Anthony Burgess asked me.

It was 1971. We were drunk at the West End Bar across from Columbia University, where I was taking Burgess’s graduate class in writing. He was going on Johnny Carson because of Kubrick’s adaptation of A Clockwork Orange. In class, Burgess polished the stories he intended to use on TV—including The Doctor Is Sick, his story about being diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1959, which spurred him to write five novels in one year in order to leave his wife enough money as possible.

By the time I knew him, Burgess had a ruined face—heavy lidded (a little like Paul McCartney if McCartney had lived Keith Richards’ life).

Burgess’s classes were supportive, unlike some of Columbia’s graduate-writing classes—competitive and bloody-minded. In one class taught by Richard Elman—one “l” not two; one “n” not two (the novelist not the biographer)—one student attempted suicide after Elman delivered savage criticism of her work. She showed up in class with her slashed wrists bandaged. The only, other, writing teacher who forbid savage attacks (Tillie Olsen) explained, “Writing is so hard, we should honor anyone who has the courage to try.”

Unlike Elman and other teachers, Burgess encouraged all of his students, trying to teach them how to get from here to there. Most of us didn’t have a clue about getting published, although Richard Price and Erica Jong were already making waves, in the same couple of years.

“You should read Ovid’s Metamorphoses,” Burgess told me.

Ovid was, Burgess suggested, my authorial father.

Burgess had sent my novel—the manuscript that caused him to tell me I should read The Metamorphoses of Ovid—to one of Knopf’s editors, who rejected it and asked Burgess if he really thought my work “deserved a Borzoi imprint,” adding that it read as if it had been written under the influence of some sort of drug—which, of course, it had (since it was 1971).

This was the sixth, unpublished novel I had written. I felt I had hit a wall when Knopf turned it down—zero for six. I was desperate.

Not too long before, a couple-of-dozen Newsday writers had written and published (pseudonymously) a dirty book, Naked Came The Stranger, which became a best seller—the Fifty Shades of Grey of its era. (Thirteen weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list.) A few years earlier, Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg’s anarchic erotic novel, Candy, had been turned into a movie.

Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious Yellow—a Swedish erotic movie—had become an underground hit in 1968. The porn movie, Deep Throat, would shatter barriers between underground and above-ground movies in 1972. Plato’s Retreat—a swingers’ club opened in 1977—would attract writers, actors and celebrities for nightly orgies.

Collaborating on literary, pornographic novels seemed a not-unreasonable thing to do. We both needed money—writers always need money.

We both researched dirty novels over the next few weeks and concluded that each chapter had to have three, sex scenes—each sex scene more extreme than the previous. We alternated chapters. By the third chapter—a woman made love to a typewriter carriage—we had reached the end of our bag of tricks.

“It’s not the lack of sexual scenarios that bothers me,” Burgess had said. “What bothers me is our lack of humanity,” which would allow us to take seriously people’s deviant desires.