WHAT IS IT ABOUT BLONDES?

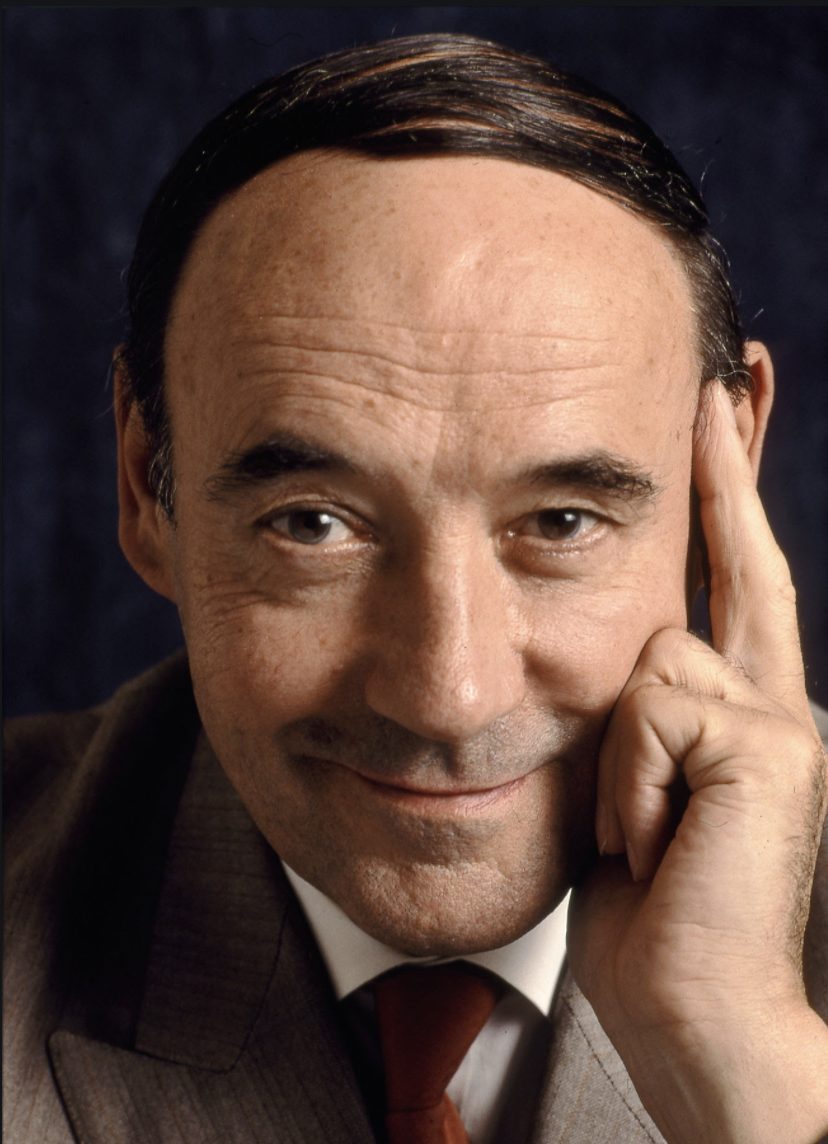

World-renowned anthropologist Desmond Morris solves an age-old mystery: What IS it about blondes? Tweet

Highlights

There are legitimate, anthropological reasons why men are drawn to blondes.

The average-blonde head has far more strands than a brunette’s or redhead’s and is softer to the touch.

Blondes transmit “take care of me” signals, heightening sex appeal.

Historically, blondness has been associated with innocence—and its polar opposite.

Editor’s Note: Desmond Morris, author of the classic, “The Naked Ape,” is among the world’s greatest ethologists and students of human sociobiology. Here, he turns his attention to a question with which men have grappled since the beginning of time.

AN ELDERLY, ENGLISH EARL of my acquaintance once confessed to me a weakness for thrusting live bats into the hair of his female houseguests. He was, in fact, conducting a series of tests to find out whether there was any truth to the old, wives’ tale—if a bat flies into a woman’s hair, it becomes hopelessly entangled.

He had already established the hair of brunettes do not become entangled—bats slipped free in a matter of seconds. But he wondered if blondes might be a special case. There is more to blondeness than color alone, he explained. The average-blonde head, for starters, is adorned with a far greater number of hairs than that of a brunette or redhead. The average number of follicles for blondes is 150,000; for brunettes, roughly 108,000; and for redheads, a mere 90,000. Blondes have thinner, softer, silkier strands than other women, as a result.

Might the blondes’ finer, denser hair more readily enmesh a wayward bat? No, apparently not. Even the shimmering cascades of blonde heads were safe from the dreaded, bat attacks.

Still, the old earl was onto something. For part of blonde appeal is the unusual thinness of the strands does make them genuinely softer to the touch and therefore more sensuous in moments of intimate, body contact. Under stroking, male fingers, or against the male cheek, the softness of the hair echoes the softness of rounded, female flesh, with its much greater fat-padding. Blondes are more feminine than darker shadings in that sense.

Side-by-side association of blondeness with virginal innocence and wickedness…has survived down the centuries.

Indeed, the femininity of blondeness extends over the whole body. The fineness of the hairs on pale skin makes blondes’ body hair less conspicuous than that of dark-haired women; even though, in actual number of strands, they are probably hairier than those of their sisters with darker heads. Blondes’ armpits and pubis are more delicately hirsute, in particular. Her pubic hairs’ soft silkiness contrasts strikingly with the aggressive, wire-brush bristliness of brunettes’.

It has even been suggested by some diligent, field workers that blondes have a different, body fragrance than other women do, making them more sexually appealing. Blondes exude a delicate scent of ambergris, contrasting with the violet scent of redheads and muskiness of brunettes, Galopin, a late-19th-century French doctor claimed—I have heard. It is not clear whether his conclusions are statistically valid, but there may well be subtle differences in scent production in various complexions of human species—simply because these originated as reactions to differing climates. We already know blondes can have fewer, sweat glands per square inch of skin when compared with most brunettes.

A second clue to the mystique of blondeness is its suggestion of youth. Babies are blonder than their parents, and “baby blues” and “blond locks” become indelibly associated with childhood, for a larger section of humanity. Such an image, when projected by an adult human female, transmits intense “take care of me” signals that can greatly heighten sex appeal.

Yet part of its allure is often an innocent, almost-inadvertent sex appeal. Pale hair and skin in Western culture have long been linked with the reassuring lightness of day and a symbolic purity. It is not by accident that in story books every maiden in distress, fairy princess and angel were crowned with pale, golden tresses—while every vixen, shrew and villainess were topped off with black, threatening tendrils of hair. The contrast was extreme, crude and persistent.

Little wonder that from empires of the ancient world to salons of baroque Europe, generation after generation of dark or mousy-haired women streamed to wig makers and hair dyers for the latest styles and potions, intent on making themselves blonder than nature intended. The ancient Greeks employed a pomade of yellow flower petals, a potassium solution and colored powders that, alas, occasionally had side effect of proving lethal. Roman ladies dyed their hair with a German soap or wore wigs made of fair, human hair of Northern Europeans—a fashion that became so widespread that Roman poet Martial mocked it with the lines: “The golden hair that Galla wears/Is hers—who would have thought it?/She swears ‘tis hers, and true she swears/For I know where she bought it.”

Ironically, or maybe not, enthusiasm for artificial blondeness very soon altered the meaning of the term or at least gave it a double meaning, with a distinction made between true blondes as virginal/innocent and fake blondes—for going to such trouble to enhance their sex appeal—as the opposite. Blonde wigs eventually became conflated with professional sexuality in Rome that its prostitutes were required by law to wear them—other, Roman, party girls also got in on the act. Wild nymphomaniac and third wife of Emperor Claudius, Valeria Messalina, would sneak out at night, clad in a whore’s wig and prowl the city for brutal sex with strangers.

Side-by-side association of blondeness with virginal innocence and wickedness/abandon has survived down the centuries. Indeed, in our own non-judgmental day, women move seamlessly from one to the other. Marilyn Monroe, who’d painfully bleach her pubic hair to match her (supposedly) platinum tresses, could by turns be squeaky-clean wholesome and sex incarnate. Madonna vamps around the stage in lingerie, singing “Like a Virgin.”

As for us men, we often don’t know the real from the fake or understand the nature of the attraction. Then again, given our nature, we don’t particularly care.

More From Desmond Morris