Mastery of Self: The Life Lessons of Admiral Stockdale

The consolations of philosophy are familiar to many prisoners, from Boethius to Admiral Stockdale. Tweet

Highlights

Captured by the North Vietnamese, Stockdale endured seven-and-a-half years of confinement and torture.

The Greek philosopher Epictetus has "been in combat with me, in leg irons with me, spent month-long stretches in blindfolds with me."

After his release Stockdale received the Medal of Honor. Though crippled in body the Navy kept him on active duty.

"Never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality."

On September 9, 1965, a Navy pilot flying at treetop level over North Vietnam ran into a flak trap. Controls useless, plane on fire, he ejected. In the 30 seconds it took him to reach the ground he whispered to himself, “Five years down there, at least. I’m leaving the world of technology and entering the world of Epictetus.”

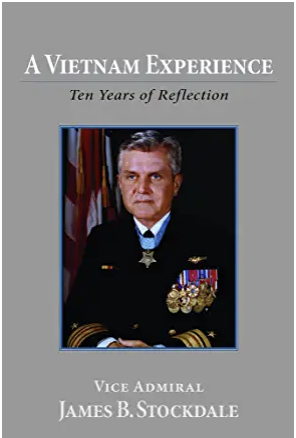

That man was Admiral James Stockdale, the “philosophical fighter pilot” and over the next seven-and-a-half years he endured confinement and torture with the help of a man born a slave who became teacher to an emperor.

Admiral James Stockdale, the “philosophical fighter pilot” endured years of confinement and torture with the help of a man born a slave.

The first thing that happened to him was being dog-piled and beaten until a North Vietnamese officer intervened and took him into captivity.

Epictetus. (Wiki)

Torture during capture permanently damaged his leg, which was oddly appropriate since the Stoic philosopher Epictetus had likewise been lamed as a Roman slave.

Previously Stockdale’s career was distinguished but no more so than many officers. He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1947, was accepted for flight training in 1949, and trained to be a Navy test pilot in 1954 where he tutored a Naval aviator named John Glenn in math and physics.

In 1962, he earned an MA at Stanford University in international relations and comparative Marxist thought. But he didn’t care for the scholarly life, preferring life as a fighter pilot.

However, at Stanford chance acquainted Stockdale with Stoicism when philosophy professor Phil Rhinelander gave him a copy of Epictetus’ book because, “He thought Epictetus and I would make a good pair.”

Stockdale later said, “He’s been in combat with me, leg irons with me, spent month-long stretches in blindfolds with me, has been in the ropes with me, has taught me that my true business is maintaining control over my moral purpose, in fact that my moral purpose is who I am. He taught me that I am totally responsible for everything I do and say; and that it is I who decides on and controls my own destruction and own deliverance.”

And the consolation of philosophy is something he would need, in and out of prison camp. Earlier, on August 2, 1964, he had led Fighter Squadron 51 as they engaged North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin.

But two nights later Stockdale had what he described as “the best seat in the house” as Navy destroyers fired at radar ghosts in an empty sea.

This was the second Gulf of Tonkin incident which President Lyndon Johnson used as a pretext to begin the bombing of North Vietnam, starting the chain of events that would lead to Stockdale’s capture.

And it was the source of a great moral ambiguity Stockdale had to deal with on top of torture, and demands for information and statements condemning his country. He feared the North Vietnamese would force him to reveal the pretext for the bombing campaign was a fraud.

“I had the wisdom of Clausewitz’ stand on moral integrity demonstrated to me throughout a losing war as I sat on the sidelines in a Hanoi prison. To take a nation to war on the basis of any provocation that bears the smell of fraud is to risk losing national leadership’s commitment when the going gets tough. When our soldiers’ bodies start coming home in high numbers, and reverses in the field are discouraging, a guilty conscience in a top leader can become the Achilles heel of a whole country. Men of shame who know our road to war was not cricket are seldom those we can count on to hold fast, stay the course.”

Yet Stockdale followed his duty and assumed command of the American POWs and created a code of conduct for their behavior under torture and organized secret communications. When he was to be paraded before cameras he slit his scalp with a razor and beat his own face to disfigure himself.

Stockdale endured being confined in leg irons, regular beatings, being confined in stress positions, and lack of medical attention.

Back home his wife Sybil organized The League of American Families of POWs and MIAs. In 1968, the organization called for the president and congress to publicly acknowledge the mistreatment of POWs and made these demands known at the Paris Peace Talks.

Stockdale was released in 1973 and in 1976 received the Medal of Honor. Though crippled in body the Navy kept him on active duty, promoting him several times. He served as president of the Naval War College and after retirement as president of The Citadel, fellow of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, and chairman of the White House Fellows under the Reagan administration.

But there were further trials to come. Stockdale accepted a request by Ross Perot to become his running mate in the presidential election of 1992 as a favor for Perot’s work on behalf of POWs, with the understanding he would be replaced on the ticket. Due to Perot’s erratic behavior he was blindsided by an interview he went into unprepared; then, using his opening remarks at the vice presidential debate to set up what he hope would be a philosophical discussion — “Who am I? Why am I here?” – he bombed badly, and was widely ridiculed as a slow-witted buffoon.

Stockdale met this as he met all the trials of his life, with Stoic fortitude.

Author James C. Collins once asked Stockdale what was characteristic of those who did not survive.

“Oh, that’s easy, the optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart. This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

The Stoic principle that enabled Stockdale and others to survive, when nothing else is under your control there is one thing you can always control, your attitude towards life.