The Adams Family: Our Founding Chick Flick

'John Adams' may be the story of every great marriage in which a smart man is made smarter by hiding behind the skirts of an ultra-smart woman. Tweet

Highlights

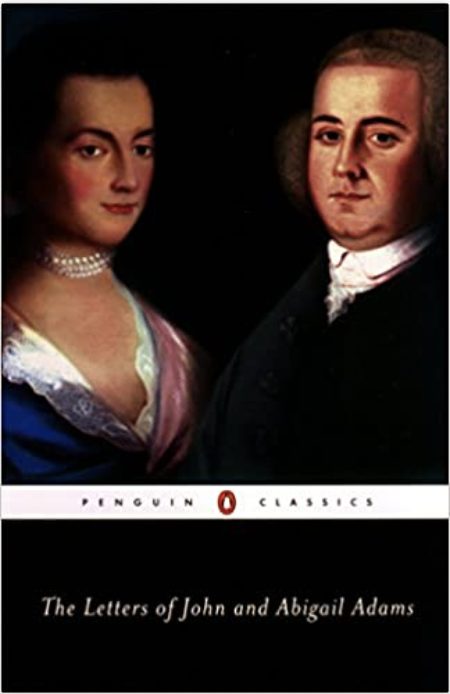

Behind every founding father...

...is one smart mama. Meet Mrs and Mr Adams.

My wife and I just watched the first episode of HBO’s John Adams, starring Paul Giamatti as John and Laura Linney as Abigail. I am always looking for a good series that I can watch with Mrs. Shepherd. This one might prove to be the best chick flick ever!

Linney’s Abigail Adams is at the midpoint between Yellowstone’s Elizabeth and Jane Austen’s ideal women: Elizebeth and Emma. I know I’m giving this series a sincere “three thumbs up” in the first episode out, but I am going with it. Abigail Adams is the feminine ideal made American real. She is a woman you want to do time with.

I had just gotten home from a six-day transcontinental trip—most of it pleasure-related–and I was knackered. I knew if I sat down and indulged my decompression viewing habits with a little South Park, Mrs. Shepherd would give a behind-the-back, melancholy shake of her head and go off to bed with a sense of marital regret. So I went to my Prime account, which provides the Shepherd’s viewing options, and convinced her to stay. I thought I would give HBO a roll of the dice. And there it was, the Adams family—as told by David McCullough (one of the greatest of living historical biographers).

Mrs. Shepherd said, “This is an American woman. Can we binge watch this together?” I’m nodding yes before she can finish the question.

At the end, Mrs. Shepherd said, “This is an American woman. Can we binge watch this together?” I’m nodding yes before she can finish the question.

The cast is first-rate. As you would expect, Giamatti is exceptional. John Adam’s ambition is just a flicker of what burns in the character Chuck in Billions but there is more to his manly mix in this. I’m a huge fan of Wendy Byrde, Ms. Linney’s character in Ozark, who is a strong, capable and articulate woman. In John Adams, She plays the role of Abigail Adams with a deftness that is smart, American and sexy. It’s said, behind every great man is a great woman. With regards to Abigail Adams this is self-evidentially true. John Adams married well. (Ozark‘s Marty Byrde less so). Abigail Adams is a woman in full.

If Jane Austen were to give an American expression of ideal femininity, it would be Abigail Adams. Abigail lacks freedom from necessity, like a typical Austen character: this is not Dickens. I have to admit Austen’s femme ideal, Emma, with her aristocratic background, brings out the Bolshevik in me and clouds my appreciation. (I can’t watch Crown for the same reason.)

The series starts with John Adams coming home on a freezing 1770’s night on horse back, entering into a cold home and warming his weary, middle-aged dad bod at the family fire.

The framing immediately shifts with a shout of “fire!”—which summons all the men of Boston to come out with water buckets and hand-pumping water wagons. While running to what we think is a building on fire, he encounters a crowd running away from something much bigger, much hotter. Instead of following the wisdom of the crowd, he runs toward the heat and finds himself in the immediate aftermath of an American origin story—the Boston Massacre—where British soldiers purportedly opened fire on “mostly peaceful protesters.”

Adams is shown immediately as manly mixture of courage, ambition and principle. Adams is a man of the law with a sense of his own destiny. He’s a newcomer to Boston, having recently relocated his family there because that was where history was happening. The day after the Boston Massacre, March 6, 1770, he was given his curtain-call opportunity.

Defending the Redcoats in Boston was much like agreeing to be the defense lawyer for Derek Chauvin. By any self-interested calculus, the downside would be as tremendous in defeat as in victory. Spoiler alert: Adams got the British soldiers off.

How he threaded the needle of victory—and got a seat at the founding brothers’ table —involves the determinative counsel of this wife. Adams shared the important matters of his mind with his partner, Abigail, a woman who had a powerful, collaborative mind of her own. There is an economy of wisdom in her speech. She is a perfect complement to someone who makes his living with his tongue. Abigail contributes a clarity of thought to her husband’s cause, something naturally lacking in someone who finds himself in the center of a shit storm.

Let’s start this study of Mrs. America’s wisdom where it is most important: in the framing of Adams’ closing argument on which her husband’s career — and the necks of those British soldiers — hangs in the balance.

Laying in bed reading, with Adams pacing outside and seeking affirmation, she says:

“You have overburdened your argument with ostentatious erudition. You do not need to quote great men to show you are one.”

How deftly she does this. She knows her man. Adams is a man of historical, common-law destiny. He is ambitious, and without her, most likely ambitious to a fault. He sees himself not only standing on the shoulders of greatness, but great himself. His wife knows he has the shoulders for this moment. He gives his reasons behind his reliance on quoting the great men of the past. But her rejoinder reorders and focuses his mind.

The next scene has her in the upper balcony of the court, watching her man, and when John catches her eye, he begins with a quotation that summons the authority of the grave and reminds me of what it was like to watch Apollo 13 with folks who understood the historical record. Adams limited his appeal to authority and brought his A-game defense which not only gave those Redcoats the defense they deserved, but also articulated a standard that carried the day, one that contributed at the dawn of American Revolution to distinguished us from the French.

Abigail had the popular touch because she understood how society—and the folks that populated it—thought. Rather than craft an argument around the elephant in the room, recognize it, give expression to it, recognize the justice behind it, and the anger and frustration that animates it. Doing so opens the mind of the jury—and the mind of fellow citizens—to persuasion, to argument rooted in principle and the proper desire of a free people to be free.

This marriage was a partnership that was ahead of its time—and our times would be better if we all could be like Abigail and John Adams.

Ask your Abigail to sit and watch it beside you. I think there is a great benefit in watching this series together.

Best,

The Shepherds.