Great American Stories: The Hallowed Ground of Gettysburg

On this date in 1869, a handful of soldiers and officers who'd fought on the storied fields at Gettysburg returned to the scene of the decisive battle. Tweet

On this date in 1869, a handful of soldiers and officers who’d fought on the storied fields at Gettysburg returned to the scene of the decisive battle. Although this would change in years to come, four years after the end of the Civil War only a few Southern combatants made the return trip to the rolling Pennsylvania countryside. For one thing, the barriers to travel were formidable. Complimentary train tickets were offered to Union veterans, but rail service in the South was spotty in 1869. It was also apparently too soon for the men who fought in Robert E. Lee’s shattered army to be attending reunions.

In the fullness of time, all that would change, as I wrote five years ago in this space. Gettysburg would be an iconic destination for veterans on both sides — and for millions of Americans not yet born. It would become one of the first four national battlefield parks and eventually a national park itself.

The idea for the 1869 Gettysburg reunion apparently originated with a Republican lawyer and local politician named David McConaughy. A Gettysburg College alum, McConaughy served in the Union Army as a scout and an intelligence officer. He was a committed abolitionist who’d supported Abraham Lincoln early in the 1860 election cycle. After the war McConaughy took the initiative in preserving Gettysburg’s battlefields in a way that furthered reconciliation and that I believe would have pleased Lincoln. Those efforts really reached critical mass in 1888, the 25th anniversary of the battle.

Here, from a National Park Service webpage devoted to the Gettysburg park, is a description of that occasion:

The veterans, averaging in their fifties, began arriving in Gettysburg in the last week of June 1888. Over the next several days, thousands of Union veterans once again descended upon the town, but just a little more than three hundred Confederates were able to attend. For most Confederate veterans, the journey was either too far, too expensive, or the invitations had arrived too late for some to make plans to attend. One newspaper estimated that there were up to 30,000 veterans, soldiers and civilians, on the battlefield. It was noted that no gathering since the battle “has equaled that of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the great event.”

The most notable headliner at the 1888 reunion was former Confederate general James Longstreet. The unofficial masters of ceremonies for each side were former Union Army general Daniel E. Sickles, a polarizing and controversial former (and future) congressman whose nickname (“Devil Dan”) said it all, and Georgia Gov. John B. Gordon, who had commanded a brigade at Gettysburg as one of “Lee’s Lieutenants.”

When Gordon spoke, he expressed the hope that Gettysburg would become “a Mecca” for Southerners as well as Northerners. If these officers carried great inner burdens about what they had ordered their men to do on the first three days of July in 1863, they also bore visible evidence of their own combat experiences. Gov. Gordon’s handsome face had been rendered cruel-looking courtesy of a deep scar from a Yankee bullet. Devil Dan lived half his life with one leg: He’d lost the other one at Gettysburg.

“Twenty-five years have passed, and now the combatants of ’63 come together again on your old field of battle to unite in pledges of love and devotion to one constitution, one Union and one flag,” Sickles told the crowd. “Today there are no victors, no vanquished.”

Under Sickle’s leadership on Capitol Hill and David McConaughy’s on the ground in Pennsylvania, the historic fields of Gettysburg were in the process of being acquired by the federal government. After a local railway company objected, eminent domain was invoked, and the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Writing for a unanimous high court, Justice Wheeler Peckham provided a nice description of why Gettysburg belongs to all the people of this country — and why we have a national park system itself:

The battle of Gettysburg was one of the great battles of the world. … The existence of the government itself, and the perpetuity of our institutions depended upon the result. … Can it be that the government is without power to preserve the land, and properly mark out the various sites upon which this struggle took place? Can it not erect the monuments provided for by these acts of Congress, or even take possession of the field of battle, in the name and for the benefit of all the citizens of the country, for the present and for the future? Such a use seems necessarily not only a public use, but one so closely connected with the welfare of the republic itself as to be within the powers granted Congress by the Constitution for the purpose of protecting and preserving the whole country.

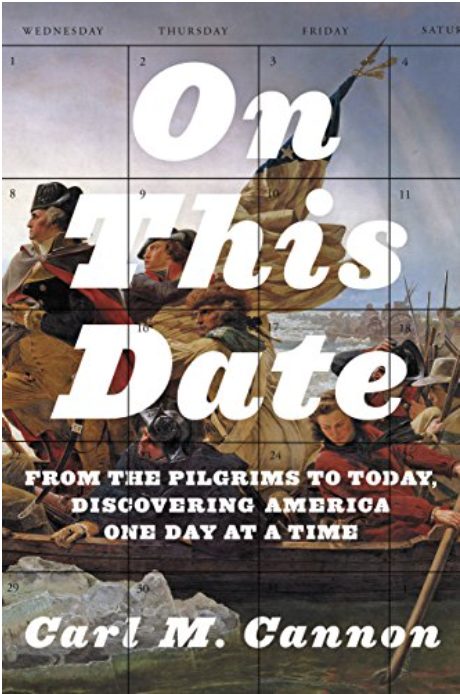

Carl M. Cannon is the Washington bureau chief for RealClearPolitics. Reach him on Twitter @CarlCannon.