Great American Stories: Sherman, ‘The Searchers,’ and Myths

On this date in 1875, a band of Apache Indians battled a unit of Texas Rangers near the Concho River. The indecisive skirmish was one of hundreds of lethal 19th century encounters between Plains Indians and white soldiers, civilians, or paramilitaries. Tweet

On this date in 1875, a band of Apache Indians battled a unit of Texas Rangers near the Concho River. The indecisive skirmish was one of hundreds of lethal 19th century encounters between Plains Indians and white soldiers, civilians, or paramilitaries. This one had a footnote, however. It seems that James B. Gillett, who had joined the Texas Rangers earlier that year, had one of the warriors in his gunsights when he froze. This Apache, whom he estimated to be 15 or 16 years old, had bright red hair. “To my surprise,” Gillett later wrote in his memoir, “he was a white boy.”

Gillett was right about that, although if the situation had been reversed the fair-haired brave — who escaped that day — would not have hesitated to pull the trigger. We know this because he later wrote his own memoir. By that time, he was no longer an Apache; he was a Comanche. Or rather, an ex-Comanche, although that’s a bit like saying “ex-Marine.”

After the Civil War, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman eschewed electoral politics to continue his career in the U.S. Army. Six years later, Sherman was camped in the Texas Hill Country on his way to a garrison called Fort Mason, when a “respectable-looking woman,” as she was described by one of Sherman’s men, approached the encampment alone.

Gen. Sherman was at that time the most feared man in the South, but this woman, a German immigrant named Augusta Buchmeier, saw him as a potential savior. A year earlier, her two sons had been plucked out of a field by raiding Indians, strapped to a horseback, and carried off. The younger boy, 8-year-old Willy, had been rescued, but 11-year-old Herman was still out there. Please, she beseeched Sherman in her accented English, can the Army find him?

Sherman listened attentively and probed for details, starting with the most basic: Which Indians took him?

“I suppose they were Comanches,” his mother responded. “He is still in their hands.”

Herman Lehmann was the boy’s name (his father, who had died, was Mrs. Buchmeier’s first husband). His mother was half right about Herman’s whereabouts. He’d originally been kidnapped and kept by Apaches and adopted their language and customs. But after a falling out, he had been taken in by Comanches, the sworn enemy of the Apache tribe and the unparalleled horsemen of the Southern Plains.

As he grew into manhood, Herman rode with the Comanches, learning their ways and their tongue, forgetting the German and English languages — and eventually his christened name name. As a brave named Montechema, Herman Lehmann raided with Comanches, married into their band, and became a formidable warrior.

For two centuries, whites had viewed these kinds of abductions as the worst kind of outrage, especially when it was white women and girls who were taken. What awaited female prisoners was sometimes gang-rape or murder. Or the story could go the other way, to the type of assimilation Herman Lehmann underwent, which in the case of stolen girls meant taking a warrior for a husband and having Indian children. Some whites had even more trouble with this outcome.

As author Glenn Frankel noted in “The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend,” real-life tales of Indian captivity dominated American bookshelves for the better part of a century. “But it was the novels of James Fenimore Cooper in the early 19th century,” he wrote, “that most openly focused upon the sexual obsession underlying the captivity narrative.”

Unlike the beautiful sisters in “The Last of the Mohicans,” Herman Lehmann was real. So was Cynthia Ann Parker, abducted during a bloody 1836 Comanche raid on the Texas frontier. In recent years, two excellent books — Frankel’s authoritative one and S.C. Gwynne’s “Empire of the Summer Moon,” have centered on Cynthia Ann Parker’s saga. The lessons found there are anything but tidy.

Cynthia was not harmed in captivity and, like Herman Lehmann, found a life to her liking among the Comanches. One of her two sons, Quanah, would become an acclaimed warrior and a chief, and is probably the man most responsible for preserving what is left of Comanche culture.

It was Quanah Parker, ultimately, who agreed to bring in the last of the Comanche warriors, a tiny band that Herman Lehmann, who was one of them, dubbed “the famous fifteen.” Two years after he was nearly shot by a Texas Ranger, Montechema was persuaded to ride into the white man’s fort by Quanah, the only person who could have done so.

All these years later, it’s not quite right to say that the anger fueled by stealing children like Herman Lehmann and Cynthia Ann Parker was manufactured. But it can be said that the whites’ horrified reaction to these abductions, and their obsession with rescuing or avenging the hostages, was a convenient rationalization for the fact that whites were overrunning and killing Indians in nearly every corner of this continent.

One man who saw that clearly was Herman Lehmann himself. “I have always found the Comanches to be my most devoted friends,” he told an interviewer in 1906. “Don’t you believe that the Comanche is a bad man. You hate him … but the Comanches don’t keep books and their side of history has never been written.”

Lehmann, who was eventually reunited with his mother and original siblings, also wrote this:

It will be remembered that Texas had refused to make a treaty with the Comanches, but by force had driven them from the land of their inheritance. For this cause many hundreds of white families, men, women and children, had come to a horrible death, while on the other hand many a brave Comanche with his wife and children had gone to the happy hunting ground. Even the old chief, Quanah’s father, had died in battle, and his mother, sisters and brothers had been carried off into captivity, never more to enjoy the blessing of Quanah’s companionship or to drink of the free air on which an Indian lives. What would have been the outcome if instead of doing evil to the Indian the white man had done good, we can only conjecture.

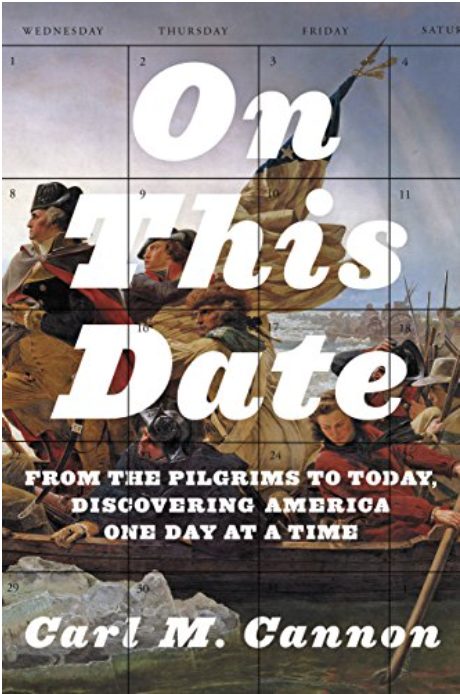

Carl M. Cannon is the Washington bureau chief for RealClearPolitics. Reach him on Twitter @CarlCannon.